Abstract

The large void space of organic electrodes endows themselves with the capability to store different counter ions without size concern. In this work, a small-molecule organic bipolar electrode called diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tris(phenoxazine) (DQPZ-3PXZ) is designed. Based on its robust solid structure by the π conjugation of diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine (DQPZ) and phenoxazine (PXZ), DQPZ-3PXZ can indiscriminately and stably host 5 counter ions with different charge and size (Li+, Na+, K+, PF6− and FSI−). In Li/Na/K-based half cells, DQPZ-3PXZ can deliver the peak discharge capacities of 257/243/253 mAh g−1cathode and peak energy densities of 609/530/572 Wh kg−1cathode, respectively. The Li/Na/K-based dual-ion symmetric batteries can be constructed, which can be activated through the 1st charge process and show the stable discharge capacities of 85/66/72 mAh g−1cathode and energy densities of 59/50/52 Wh kg−1total mass, all running for more than 15000 cycles with nearly 100% capacity retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic redox-active compounds have attracted numerous attentions and been emerging as the promising electrode materials due to their unique nature such as abundant element resources, low cost, and high energy density1,2,3,4. Moreover, it has been unveiled by the accumulated research papers that organic electrodes possess the distinctive electron-storage and ion-storage mechanisms when compared to inorganic electrodes in rechargeable ion batteries5,6,7,8. The essence is that whether in crystal state or amorphous state, organic solids are mainly composed by single molecule aggregated by Van der Waals forces and thus can provide enough void space to accommodate different counter ions9,10,11. Specifically, electrons are reversibly stored in the frontier orbitals of each organic molecule (e.g., HOMO=highest occupied molecular orbital and LUMO = lowest unoccupied molecular orbital), whereas counter ions are reversibly intercalated into the positive-charged or negative-charged functional groups of each organic molecule12,13. Consequently, organic electrodes in principle possess “single-molecule-energy-storage” capability and are supposed to demonstrate the similar storage mechanism for different counter ions.

However, most small-molecule organic electrodes suffer from serious dissolution problem in liquid electrolytes, which hinders their practical application in rechargeable ion batteries14,15,16. Furthermore, recent research results reveal that solvent molecules from liquid electrolyte can co-intercalate along with the intercalated counter ions into the organic electrodes during redox reaction, resulting in the destruction of organic solid structure and energy reduction of the whole system17,18,19. As a result, the battery performance of organic electrodes is very sensitive to the counter ions and the electrolytes. Even if one organic electrode is found to be suitable in Li-ion batteries, it might be difficult to achieve the satisfactory battery performances in Na-ion and K-ion batteries20,21,22. While the polymerization of organic molecules seems to be a feasible method to solve the dissolution and solvent-molecule co-intercalation issues based on the robust solid structure, the large proportion of inactive units and the purification complexity hinder the further development of insoluble organic polymer electrodes23,24,25,26. Consequently, the capability of organic electrodes for stably storing different kinds of counter ions is not widely realized by the battery community.

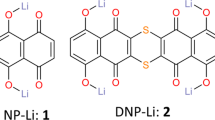

Delightfully, the above concerns can be well addressed by designing insoluble small-molecule organic electrodes with robust solid structures. In fact, the insolubility of small organic molecules means the inter-molecular π-π interaction forces are stronger than the solvation forces provided from solvent molecules. More specifically, these insoluble organic molecules usually possess very large π aromatic conjugation skeleton. For example, perylene with 5 conjugated aromatic rings shows poor solubility against most organic solvents. Following the above molecule-design principle, our group initially reported an organic molecule called [N,N’-bis(2-anthraquinone)]-perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxydiimide (PTCDI-DAQ) with a high theoretical specific capacity (CT) of 200 mAh g−1 in 2020 (Fig. 1a-I). PTCDI-DAQ structurally bearing the perylene core can show the expectable insolubility for most organic solvents. As a result, PTCDI-DAQ can deliver very impressive cathode performances in all Li/Na/K-ion batteries13,27,28,29. However, PTCDI-DAQ is a n-type organic cathode with a low redox potential (1.0-3.8 V vs. metal anode) and it is unable to store counter anions.

In this article, we design an insoluble small-molecule organic electrode called diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tris(phenoxazine) (DQPZ-3PXZ), in order to prove that organic electrodes can stably and reversibly store not only metal cations (such as Li+/Na+/K+), but also the bigger counter anions (such as PF6−/FSI−=bisfluorosulfonimide) within single molecule structure. As depicted in Fig. 1a-II, DQPZ-3PXZ structurally features the n-type diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine (DQPZ) core with very large π aromatic conjugation (7 conjugated aromatic rings). Notably, DQPZ can show the 6 electron CT of 418 mAh g−1 and is initially applied in Li-ion batteries by Matsunaga and co-workers (2011)30. Fair cathode performances of DQPZ were reported in Na-ion and K-ion batteries31. Meanwhile, we add three phenoxazine (PXZ) units to the periphery of DQPZ core with the following two purposes: i) PXZ with 3 conjugated aromatic rings can further extend the π conjugation of the whole DQPZ-3PXZ molecule; ii) PXZ is a p-type organic motif with the reversible one-anion-inserted redox process32,33,34. Nevertheless, PXZ is highly soluble and it shows poor anion-storage stability33.

With these above merits, the designed DQPZ-3PXZ can show the high 9-electron redox capacity of 260 mAh g−1. Meanwhile, DQPZ-3PXZ with n-p molecular configuration possesses the bipolar electrode property and thus can be used to construct symmetric batteries with the CT of 87 mAh g−1 based on its 3-electron cathode part. Remarkably, symmetric batteries are interesting energy storage devices based on bipolar electrodes, where a single bipolar electrode acts as both cathode and anode in the battery system35. The utilization of bipolar electrodes can significantly reduce the production cost and simplify the battery fabrication process36,37. Nonetheless, the examples of bipolar electrodes and symmetric batteries are extremely limited36,37,38,39,40,41,42, especially for the cases reported in the K-based symmetric batteries43,44. More seriously, the majority of symmetric batteries suffer from poor cycle lifespan, far away from real applications40.

Here, as confirmed by the cyclic voltammetry (CV), ex-situ Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) results, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and ex-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, the n-type DQPZ core of DQPZ-3PXZ can indiscriminately store Li+/Na+/K+ cations and simultaneously its p-type PXZ motifs can stably store the bigger PF6−/FSI− anions, respectively. Consequently, DQPZ-3PXZ can deliver very similar peak capacities of 257/243/253 mAh g−1cathode for the assembled Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively. Meanwhile, DQPZ-3PXZ can exhibit unprecedented bipolar electrode performances in three Li/Na/K-based dual-ion symmetric batteries (Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs). All three kinds of symmetric batteries can be simply activated by the 1st charge process and show the stable discharge capacities of 85/66/72 mAh g−1cathode with the median voltage of 1.36/1.34/1.43 V (59/50/52 Wh kg−1total mass), respectively. More strikingly, based on its robust solid structure, all three kinds of symmetric batteries can show ultra-long lifespans for more than 15000 cycles without obvious capacity decay. This work proves that DQPZ-3PXZ can be used to support the concept of “single-molecule-energy-storage” for organic electrodes and their use for dual-ion symmetric batteries.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations

The organic synthesis of diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tris(phenoxazine) (DQPZ-3PXZ) was depicted in Fig. 1b. Firstly, the key intermediate of diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tribromine (DQPZ-3Br) could be readily realized through a simple one-step condensation reaction between 4-bromobenzene-1,2-diamine and cyclohexanehexone octahydrate with the excellent yields of 90-95%. Secondly, the final product of DQPZ-3PXZ could be obtained with a high yield above 80% by the Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig C-N coupling reaction between phenoxazine (PXZ) and DQPZ-3Br in N2 atmosphere. See synthesis details in Methods. As expected, DQPZ-3PXZ shows very poor solubility for most organic solvents but a certain solubility in chloroform (<2 × 10−4 mg/mL, Supplementary Fig. 1). Consequently, we use deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) to perform its 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2a). As provided in Fig. 1c, the 1H NMR spectrum showed the distinctive and sharp H-signal peaks for DQPZ-3PXZ. There are 33 H atoms in one DQPZ-3PXZ molecule, and the integrated intensity of the H signal could confirm the correct structure of DQPZ-3PXZ. According to the reference45, the H signal (~6 H) in the chemical shift (δ) range of 8.7–9.0 ppm belonged to the two adjacent H atoms on DQPZ core, and the H signal (~3 H) in the chemical shift (δ) range of 8.0–8.2 ppm belonged to the other H atoms on the DQPZ core. On the other hand, the H signal (~24 H) in the chemical shift (δ) range of 6.3–7.0 ppm was ascribed to the H atoms on the PXZ unit. And the H-signal integrated intensity between the chemical shift (δ, ppm) of 9.0-8.0 and 7.0-6.0 was very close to the ratio of 3:8. Meanwhile, the exact mass (M+ = 927.27) of DQPZ-3PXZ could be confirmed by the result ([M + H]+ = 928.28) observed in mass spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2b). And the absence of Br element in the DQPZ-3PXZ solid could also reflect the successful synthesis of DQPZ-3PXZ (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, we collected and compared the X-ray diffraction (XRD) results for DQPZ-3PXZ, DQPZ-3Br, and PXZ. As shown in Fig. 1d, the XRD pattern of DQPZ-3PXZ manifested the different diffraction peaks from DQPZ-3Br and PXZ, and the four typical diffraction peaks (16.3o, 20.8o, 22.0o, and 26.5o) of DQPZ-3PXZ could be observed. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of DQPZ-3PXZ were provided in Supplementary Fig. 4, which demonstrated the block structure feature of DQPZ-3PXZ.

Redox mechanism

The electrochemical behaviors of DQPZ-3PXZ were initially evaluated in cyclic voltammetry (CV) for all Li/Na/K-based half cells. The neat loading mass of DQPZ-3PXZ was 60 wt% and 2-3 mg cm−2 in the electrode composition on Al foil. Notably, DQPZ-3PXZ was used as received and no other technical processing was carried out or hidden. Meanwhile, the electrolytes were selected to be 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/diethyl carbonate/dimethyl carbonate (EC/DEC/DMC), 2 M NaPF6 in diethylene glycol dimethyl ether (DEGDME), and 2.2 M KPF6 in DEGDME for the Li/Na/K-based half cells. The anodes were Li/Na/K metals, respectively. See half-cell fabrication details in Methods. The collected CV results are shown in Fig. 2a. As expected, DQPZ-3PXZ was redox-active in all Li/Na/K-based half cells. After an activation process in the 1st cycle, DQPZ-3PXZ exhibited two types of redox peaks. The first type with the lower potential was the six-metal-ion intercalation and deintercalation process of DQPZ core, where the intercalation-deintercalation process was divided by three steps31,45,46,47. Meanwhile, the second type located at the higher potential belonged to the one-anion intercalation and deintercalation process of three PXZ units32,33. In Li-based half cells (Fig. 2a-I), the redox peaks located below 3.2 V belonged to the first type of redox peaks, which included the three adjacent reduction peaks at 1.8/2.2/2.5 V and one broad oxidation peak at 2.7 V (vs. Li). The second type of redox peaks located at 3.6/3.7 V (vs. Li) belonged to the one-anion intercalation and deintercalation process of three PXZ units. In Na-based half cells (Fig. 2a-II), DQPZ-3PXZ exhibited the lower and separated first type of redox peaks at 1.3/1.4 V, 1.8/2.0 V and 2.3/2.6 V (vs. Na), resulting from the Na-ion intercalation and deintercalation process of DQPZ core. The higher potential redox peaks stabilizing at 3.0/3.1 V and 3.7/3.8 V were belonging to the second type of redox peaks for the Na-based half cells. In K-based half cells (Fig. 2a-III), after the 1st cycle, the first type of redox peaks was composed of two broad reduction peaks at ~1.4/1.9 V and three oxidation peaks at 1.4/2.2/2.4 V (vs. K), respectively. Similarly, the reduction peaks observed at 3.3/3.9 V and one oxidation peak at 4.0 V (vs. K) were the results of anion intercalation and deintercalation process of three PXZ units. Particularly, the 2-4 laps of the CV curves were nearly overlapped in all Li/Na/K-based half cells, manifesting the good redox stability and reversibility of DQPZ-3PXZ.

a The CV curves of DQPZ-3PXZ in (I) Li-based half cells (1.4–4.1 V), (II) Na-based half cells (0.7-4.0 V), and (III) K-based half cells (0.9-4.2 V) with a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. b The 2nd cycle of charge-discharge curves at different potential interval in (I) Li-based half cells, (II) Na-based half cells, and (III) K-based half cells.

In addition, to eliminate the capacity contribution from the KB conductive agent, the dQ/dV profiles at 50 mA g−1 using super P as conductive agent were performed for DQPZ-3PXZ. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 5a, the dQ/dV profiles demonstrated a clearer and more obvious step-by-step oxidation/reduction peaks of DQPZ-3PXZ electrode, which well manifested the difference in Li/Na/K-based half cells. The integrations of the reduction peaks for DQPZ core were ~1:1:1, while the oxidation peaks of DQPZ core were ~2:1/1:1:1/1:2 in Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5b). This suggested the overall 6e storage of DQPZ core in Li/Na/K-based half cells was sequential and divided by three steps46,48. Meanwhile, the peaks for three PXZ units were analyzed. For Li-based half cells, the oxidation/reduction process of PXZ units was one-step reaction suggested by the one overlapped oxidation/reduction peak at the higher potential. In contrast, the two oxidation/reduction peaks with the integrations of ~1:2 for Na-based half cells indicated that the PXZ units underwent two-step reaction in Na-based half cells. In K-based half cells, the oxidation process of PXZ units was one-step reaction while the reduction process was two-step reaction according to the integration of ~1:2. Combined with the CV results and dQ/dV profiles, the overall 9e storage of DQPZ-3PXZ was initially characterized.

In order to further verify the counter ions with different charges and sizes could be indiscriminately and stably hosted in DQPZ-3PXZ molecules, the charge-discharge curves at different intervals for the Li/Na/K-based half cells were tested. All the chosen potential intervals were based on the CV results for the Li/Na/K-based half cells. The charge-discharge curves at the lower and high intervals were shown in Fig. 2b, and the 2-4 laps of the charge-discharge curves for all Li/Na/K-based half cells were nearly overlapped (Supplementary Fig. 6), which corresponded to the previous CV results. For the lower potential interval (n-type DQPZ core), similar voltage platforms and specific discharge capacities of 173/156/159 mAh g−1 for the Li/Na/K-based half cells were achieved, respectively. These results were approaching the theoretical specific capacity that DQPZ core could deliver (6e, 173 mAh g−1). Meanwhile, the higher potential interval (p-type PXZ unit) shows similar specific capacities of 78/79/77 mAh g−1 for the Li/Na/K-based half cells, which were close to the CT value (3e, 87 mAh g−1) of three PXZ units. It is worth noting that for the Li-based half cells, there was only one voltage platform for p-type PXZ unit, while there were two distinct voltage platforms for the Na-based half cells and two distinct discharge platforms for the K-based half cells, which corresponded to the dQ/dV results in Supplementary Fig. 5, indicating that the three-anion intercalation-deintercalation processes in the Na/K-based half cells were stepwise. Conclusively, the similar specific capacities and voltage platforms observed are the basic proofs that DQPZ-3PXZ can indiscriminately and stably host 4 counter ions (Li+, Na+, K+, PF6−) with different charges and sizes.

Ion-storage mechanism

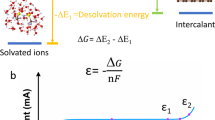

To further unveil the ion-storage mechanism of DQPZ-3PXZ in Li/Na/K-based half cells, the ex-situ FT-IR measurements and the ex-situ XPS were carried out by selecting different charge-discharge potentials in CV curves (Fig. 2a). The collected FT-IR results for the Li/Na/K-based half cells were depicted in Fig. 3a. The peak intensity (≈1583 cm−1) related to C=N bond vibration in DQPZ core gradually decreased and disappeared from the pristine state when discharging to 1.4/0.7/0.9 V for the Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively49,50,51. However, this peak (≈1583 cm−1) could reversibly recover when totally oxidizing to the highest potential in all Li/Na/K-based half cells, which indicated the metal-ion intercalation and deintercalation process of DQPZ core in DQPZ-3PXZ. Meanwhile, the resulting wide XPS spectra for Li/Na/K-based half cells were demonstrated in Fig. 3b. In the wide XPS spectra of all Li/Na/K-based half cells (Fig. 3b), there were no peak intensity of F or P content whether at the pristine state or discharged to the lowest potential. However, when charged to the highest potential, both F and P content (peak intensity) could be observed, indicating the reversible anion intercalation and deintercalation process of the PXZ unit in DQPZ-3PXZ. In the wide XPS spectra for the Na and K-based half cells, the relative Na and K content (peak intensity) appeared when discharged to the lowest potential, while these peaks vanished after charging to the highest potential, indicating the reversible Na/K-ion intercalation and deintercalation process of DQPZ core in DQPZ-3PXZ. These results were also confirmed by the C1s, N1s spectra of Li/Na/K-based half cells shown in Supplementary Fig. 746,47,52. On the other hand, the redox reactions of DQPZ-3PXZ in Li/Na/K-based half cells were also mapped by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) in Supplementary Fig. 8–10. When re-charging to the highest potential, the signal intensities of F and P elements were largely enhanced on the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode when compared to the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode with discharging to the lowest potential. So the EDS results could indicate the anion (PF6−) intercalation into the PXZ unit of DQPZ-3PXZ53. Particularly, the same reversible transformation trend of DQPZ-3PXZ was also observed in the ex-situ XRD tests by selecting different status points (A-E) during one redox cycle (Fig. 3c). The collected XRD patterns for these selected points are shown in Fig. 3d. The typical diffraction peak at 26.5o shifted to the lower angle direction whether after the charging or discharging process, indicating that the counter ions were inserted into the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode and made the solid expand27,54. Based on the above experiment results, along with the charge-discharge curves (Fig. 2b) and dQ/dV profiles (Supplementary Fig. 5), the overall 9-electron redox mechanism (including step-by-step 6-electron n-type (Supplementary Fig. 11) and three 1-electron p-type) of DQPZ-3PXZ can be proposed in Fig. 4, endowing itself a high CT of 260 mAh g−1.

a The ex-situ FT-IR spectra. b The ex-situ wide XPS spectra. c The selected points for the DQPZ-3PXZ electrodes during one cycle. d The ex-situ XRD patterns for these selected points of the DQPZ-3PXZ electrodes (I, II, III represent for Li-based half cells, Na-based half cells and K-based half cells, respectively).

Quantum calculations

To give deep insights into the redox and ion-storage behaviors of DQPZ-3PXZ, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31 G* level. See details in SI. At the beginning, the geometrical structure of DQPZ-3PXZ with a neutral state is optimized with B3LYP functional. As shown in Fig. 5a, the central DQPZ core holds a planar structure, while the three phenoxazine (PXZ) substitutes are out of the plane due to the steric hindrance of C-H bonds. The average dihedral angle between DQPZ plane and the PXZ plane is 66.69o. As expected, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is largely distributed in PXZ group, indicating it can lose (donate) electrons during the oxidation process. Meanwhile, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is mainly located on the DQPZ core, manifesting it can accept electrons during the reduction process. Furthermore, due to the symmetry of the DQPZ-3PXZ molecule, the HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2 orbitals are all the π orbitals on the PXZ substitutes, indicating all the three PXZ substitutes can lose (donate) electron during the oxidation process. On the other hand, the LUMO, LUMO + 1, and LUMO + 2 orbitals are all the π* orbitals of the DQPZ core, manifesting DQPZ core can accept as many as 6 electrons during the reduction process.

Subsequently, the geometrical structures and frontier orbitals for the reduced state and oxidized state of DQPZ-3PXZ are respectively optimized and simulated. i) The reduced states of DQPZ-3PXZ after 6-Li+/Na+/K+-ion intercalation are respectively depicted in Fig. 5b. As the reduction proceeds, the LUMO, LUMO + 1 and LUMO + 2 orbitals of DQPZ-3PXZ are all occupied step-by-step, accompanying the C-N bonds connecting the DQPZ core and the PXZ substitutes are stretched from 1.425 Å to 1.438 Å in average. Meanwhile, the occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO, HOMO-1, and HOMO-2) are re-distributed on the [DQPZ]6- core after full reduction. The inserted 6 Li+/Na+/K+ cations are situated close to the negative-charged N atoms of [DQPZ]6- core, respectively. ii) The oxidized state of DQPZ-3PXZ after 3-PF6−-ion intercalation is also simulated in Fig. 5c-I. During the oxidation process, one electron in the three PXZ substitutes can be stripped, leading to the formation of N+ atoms on three [PXZ]+ substitutes and the elongation of the C-N bonds (from 1.425 Å to 1.452 Å) between DQPZ and PXZ. Accordingly, the singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMO, SOMO-1, and SOMO-2) are all distributed on the three [PXZ]+ substitutes. At the same time, three PF6− anions are movable to the positive-charged [PXZ]+ molecular plane for electrical neutrality. In addition, the geometrical structures and orbital distributions of DQPZ-3PXZ with 3-FSI−-ion intercalation are provided in Fig. 5c-II. The frontier orbitals (SOMO, SOMO-1, and SOMO-2) are also located on three [PXZ]+ substitutes and the inserted three FSI− anions are still nearby the [PXZ]+ molecular plane.

Half cells

Subsequently, the whole cathode performances of DQPZ-3PXZ in Li/Na/K-based half cells were tested in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6a, reduction process was started in the 1st cycle. From the 2nd cycle, DQPZ-3PXZ exhibited the obvious discharge-charge potential platforms (3.7/2.2 V for Li, 3.6/1.8 V for Na and 3.9/2.1 V for K, respectively) and the peak discharge capacities of 257/243/253 mAh g−1 at the low specific current of 200 mA g−1 (Fig. 6a). Combined with the median voltages of 2.37/2.18/2.26 V, DQPZ-3PXZ could deliver the peak energy densities of 609/530/572 Wh kg−1cathode for Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively. The 2nd cycle of charge-discharge curves (x vs E) for Li/Na/K-based half cells were demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 12. In addition, the capacity contributions from carbon additive (30 wt%) were calculated to be 28/48/35 mAh g−1 in Supplementary Fig. 13, respectively. (See specific capacity calculation in Methods). The cycle profiles of DQPZ-3PXZ in Li/Na/K-based half cells were provided in Supplementary Fig. 14a, and it could maintain the stable average capacities of 229/243/220 mAh g−1 during 200/200/100 cycles at specific current of 200 mA g−1, respectively. Notably, for Li/Na-based half cells, the coulombic efficiency (CE) values were nearly 100%. However, the CE value of DQPZ-3PXZ in K-based half cells could hardly reach 100% (~93%), which resulted from the parasitic reactions on the very-active K-metal anode side15,55. Particularly, the SEM images in Supplementary Fig. 15 showed no obvious morphology change of DQPZ-3PXZ after 100 cycles, and the charge-transfer impedances (Rct) of its half cells gradually decreased after cycles in the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests (Supplementary Fig. 16). During the long-term operation at the high specific current of 1 A g−1 (Fig. 6b), the discharge capacities of DQPZ-3PXZ still remained to be 154/193/175 mAh g−1 after 1800/4000/600 cycles, with 72/84/75% capacity retentions to its peak values (213/229/234 mAh g−1), respectively. Due to the parasitic reactions on the K-metal anode side, the lifespan of K-based half cells was limited up to 600 cycles. The rate performances of DQPZ-3PXZ in Li/Na/K-based half cells were performed in Supplementary Fig. 14b. At the specific currents of 0.2/0.5/0.8/1/2/5 A g−1, DQPZ-3PXZ demonstrated the good rate capacities of 247/226/224/222/209/181 mAh g−1, 235/237/236/235/231/214 mAh g−1 and 242/228/220/219/210/187 mAh g−1 in Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively. Particularly, the rate capacities could satisfactorily afford to be 150/186/161 mAh g−1 at the high specific current of 10 A g−1 (≈39 C) with the capacity retentions of 58/72/62% to the CT value (260 mAh g−1) for Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively. On the other hand, to study the kinetics of the DQPZ-3PXZ electrodes in Li/Na/K-based half cells, galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) and variable-scan CV were carried out. According to the GITT results, the average ion (cation/anion) diffusion coefficient of the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode was calculated to be ~8.0×10−10/7.4×10−10/8.3×10−10 cm2s−1 for Li/Na/K-based half cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 17). Specifically, the average diffusion coefficient for the voltage platform of DQPZ core was higher than that of PXZ unit in all Li/Na/K-based half cells, demonstrating a faster kinetics of metal ions than the bigger anions. Meanwhile, the results of variable-scan CV curves manifested the redox behaviors of the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode in Li/Na/K-based half cells were simultaneously controlled by pseudocapacitance and diffusion process (Supplementary Figs. 18–21)53,56,57.

Symmetric cells

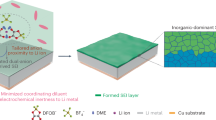

Eventually, based on the bipolar molecular configuration of DQPZ-3PXZ, the Li/Na/K-based dual-ion symmetric batteries (Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs) were constructed by using DQPZ-3PXZ as the single organic electrode material. It is very important to emphasize that no pre-treatments for the electrodes were performed, and the current collector was the low-cost Al foil on both the anode and cathode sides. The mass ratio between the cathode and anode was 1:0.5. The minimum volume of the electrolytes used was determined to be 50 μL for all Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells (See symmetric batteries fabrication details in Methods). At the beginning, the same electrolytes (LiPF6, NaPF6, and KPF6) used in half cells were chosen for fabricating Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs. Based on the electrochemical performances of DQPZ-3PXZ in half cells at different potential intervals (Fig. 2b), we determined that the voltage ranges of Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs were 0.01–2.5 V, 0.01–2.4 V, and 0.01–2.4 V, respectively. Very strangely, all the symmetric batteries demonstrated unsatisfactory performance with inconspicuous potential platforms and significant capacity decay (Supplementary Fig. 22). The detailed reasons behind the phenomena are currently under study. And one reason might be ascribed to the instability of hexafluorophosphates (PF6−), which was reported to decompose during electrochemical reactions58,59,60. To address this issue, we chose bisfluorosulfonimide (FSI−) salts to fabricate symmetric batteries, which possess a better electrochemical stability during charge-discharge cycles61. Specifically, the electrolytes were re-selected to be 3 M lithium bisfluorosulfonimide (LiFSI) in tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TEGDME), 1.5 M sodium bisfluorosulfonimide (NaFSI) in TEGDME and 3 M potassium bisfluorosulfonimide (KFSI) in TEGDME for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, respectively. All the newly-chosen electrolytes were tested in Li/Na/K-based half cells at higher potential interval (Supplementary Fig. 23), which demonstrated the more obvious potential platforms and the higher CE values than those using the PF6−-based electrolytes. Combined with the above results, it has been proved that DQPZ-3PXZ can indiscriminately and reversibly host 5 counter ions (Li+, Na+, K+, PF6− and FSI−) with different charges and sizes during its redox reaction.

Accordingly, the symmetric-cell configuration and mechanism were shown in Supplementary Fig. 24, where the n-type DQPZ core (6e CT = 173 mAh g−1) and three p-type PXZ units (3e CT = 87 mAh g−1) in DQPZ-3PXZ will serve as the negative and positive electrode roles during the discharge process, respectively. Particularly, the open voltages for all the constructed Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs were close to zero (~0.01 V) and thus they must be activated through the 1st charge process. Consequently, the fabricated Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs could deliver the 1st charge capacities of 106/99/79 mAh g−1cathode at a specific current of 40 mA g−1 during the charging process up to 2.5/2.4/2.4 V (Supplementary Fig. 25), and the 1st charge-discharge CE values were 88/94/92% for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, respectively. Gradually, the CE values for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs could reach ~100% during 50 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 26). Notably, the ~100% CE values in K-SBs could verify that the parasitic reactions on the very-active K-metal anode side were the main reason for the low CE values in K-based half cells. After stabilization, DQPZ-3PXZ exhibited the obvious charge-discharge voltage platforms and reversible discharge capacities in Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs (Fig. 7a). Specifically, the median discharge voltage platforms were 1.36/1.34/1.43 V and the stable discharge capacities were 85/66/72 mAh g−1cathode for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, respectively. The 20th cycle of charge-discharge curves (x vs E) for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs were demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 27. In addition, the capacity contributions from carbon additive (30 wt%) were calculated to be ~12 mAh g−1 for all the symmetric batteries in Supplementary Fig. 28. Notably, the realized discharge capacities were close to the 3-electron CT value of 87 mAh g−1 based on the cathode redox mechanism. Correspondingly, the stable energy densities of the fabricated symmetric batteries were calculated to be 116/88/103 Wh kg−1 based on the cathode mass, and 59/50/52 Wh kg−1 based on the total DQPZ-3PXZ mass and the inserted electrolyte mass. See calculation details in Methods. For Na-SBs, the peak discharge capacity could reach 72 mAh g−1cathode at the 1st charge-discharge cycle (Supplementary Fig. 26). However, the discharge capacity decreased at the first 15 cycles before stabilization (Supplementary Figs. 25,26). And the behind reasons were unknown at the current stage. Despite that, the 20-40th charge-discharge cycles nearly overlapped in all Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs (Fig. 7a), manifesting the good redox stability and reversibility of the DQPZ-3PXZ electrode. These charge-discharge results were well related to the CV curves for all the symmetric batteries in Supplementary Fig. 29.

Impressively, all three kinds of symmetric batteries could achieve an ultra-stable and ultra-long-lifespan profile. As depicted in Fig. 7b, under a low specific current of 80 mA g−1cathode (≈1 C), all three kinds of symmetric batteries could maintain a long lifespan over 5/8/7 months (1800/4000/3000 cycles) with small capacity decay (89/85/94% retentions for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs), respectively. At the specific current of 0.1/0.2/0.5/1/2 A g−1cathode, the symmetric batteries could exhibit the excellent rate performances with the capacities of 85/81/79/77/73 mAh g−1cathode, 66/65/60/56/51 mAh g−1cathode and 72/68/64/59/52 mAh g−1cathode in Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 30). In particular, the realized reversible discharge capacities were 64/42/33 mAh g−1cathode at the high specific current of 5 A g−1cathode (≈58 C) with the capacity retentions of 74/48/38% to the CT value (87 mAh g−1cathode) for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, respectively. More strikingly, the long-cycle stability of the three symmetric batteries at the high specific current of 2 A g−1cathode (≈23 C) was provided in Fig. 7c. All three kinds of symmetric batteries could still deliver the discharge capacities of 73/56/60 mAh g−1cathode after the ultra-long lifespans of 15000/40000/40000 cycles, along with the high capacity retention of nearly 100% (100/98/97% for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs) respectively. For K-SBs, the ultra-long lifespan could be extended to 91000 cycles (6 months) with 68% capacity retention (Supplementary Fig. 31). As shown in Supplementary Table 1, the bipolar results of DQPZ-3PXZ have already produced the world record for symmetric batteries.

Discussion

In summary, a well-designed small organic molecule called DQPZ-3PXZ with bipolar electrode property is designed and synthesized for the Li/Na/K-based batteries, which can indiscriminately store 5 counter ions (Li+/Na+/K+ and PF6−/FSI−) during its 9-electron redox reaction. In the Li/Na/K-based half cells, DQPZ-3PXZ can show the peak discharge capacities of 257/243/253 mAh g−1 as the cathode electrode. In the Li/Na/K-based dual-ion symmetric batteries, DQPZ-3PXZ can still provide the reversible and stable energy densities of 59/50/52 Wh kg−1 based on the total DQPZ-3PXZ and electrolyte mass, respectively. All three kinds of symmetric batteries can run for more than 15,000 cycles with nearly 100% capacity retention. Therefore, DQPZ-3PXZ can prove our concept of “single-molecule-energy-storage” for organic electrodes. This work opens an era for the further development of organic electrodes in rechargeable ion batteries.

Methods

Synthesis of diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tribromine (DQPZ-3Br)

4-bromobenzene-1,2-diamine (1.41 g, 7.53 mmol) was added into a 250 mL two-necked flask charged with nitrogen gas. Degassed AcOH (50 mL) was slowly injected. Thereafter cyclohexanehexone octahydrate (0.783 g, 2.51 mmol) was added under nitrogen gas flow and the mixture was stirred at 125 oC for 24 h. Then the mixture was poured onto ice water and thereafter 150 mL saturated Na2CO3 solution was added. After filtration, the residue was washed several times with water, ethanol, and acetone to give DQPZ-3Br in good yield (1.403 g, 2.27 mmol, 90–95%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, ppm, d1-CDCl3): δ = 8.9 (s, 3H, Ar-H), 8.57–8.55 (d, J = 8 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 8.16–8.14 (d, J = 8 Hz, 3H, Ar-H).

Synthesis of diquinoxalino[2,3-a:2’,3’-c]phenazine-2,6,10-tris(phenoxazine) (DQPZ-3PXZ)

Phenoxazine (0.906 g, 4.95 mmol), DQPZ-3Br (0.927 g, 1.5 mmol), X-Phos (257 mg, 0.54 mmol), t-BuONa (475 mg, 4.95 mmol) and Pd2(dba)3 (135 mg, 0.147 mmol) were added into the glass tube under N2 atmosphere, and then 45 mL toluene was added under N2 atmosphere. The mixture was reacted at 110 °C for 3 days. After cooling to room temperature, 50 mL alcohol was added and the solids were directly rinsed with water and alcohol by three times. Afterward, DQPZ-3PXZ was purified in tetrahydrofuran for 72 h through a Soxhlet’s apparatus and then dried at 100 °C to afford 1.11 g as the dark blue solids. 1H NMR (400 MHz, ppm, d1-CDCl3): δ = 8.93–8.74 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 8.10–8.06 (m, J = 8 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 6.89–6.82 (m, 12H, Ar-H), 6.76–6.72 (m, J = 8 Hz, 6H, Ar-H), 6.39–6.37 (d, J = 8 Hz, 6H, Ar-H). MS (EI, m/z): [M]+ calcd for C60H33N9O3, 927.27; found [M + H]+, 928.28. Anal. calcd for C60H33N9O3 (%): C 77.65, H 3.56, N 13.58. found: C 77.93, H 3.45, N 13.17.

Half cells

The DQPZ-3PXZ-based electrodes were simply fabricated by 60 wt% DQPZ-3PXZ, 30 wt% KB and 10 wt% La133 (binder). The neat loading mass of DQPZ-3PXZ on Al foil was >2 mg cm−2. The electrolytes for Li-ion, Na-ion, and K-ion half cells were 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC/DMC, 2 M NaPF6 in DEGDME, and 2.2 M KPF6 in DEGDME, respectively. The separator was Whatman glass fiber (thickness of 0.42 mm). The anodes were Li, Na, and K metals, respectively. All the metal anodes were pressed tightly onto the negative electrode shell for half cells. All half cells (CR2032) were assembled in the Ar-filled glove box, which were tested in the atmosphere at room temperature. CVs were tested at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 between 1.4 and 4.1 V (vs. Li+/Li), between 0.7 and 4.0 V (vs. Na+/Na), and between 0.9 and 4.2 V (vs. K+/K) using electrochemical workstation (CHI 650e). All the capacities were reported based on the mass of DQPZ-3PXZ in half cells.

Li/Na/K-based dual-ion symmetric batteries

The DQPZ-3PXZ-based electrodes were simply fabricated by 60 wt% DQPZ-3PXZ, 30 wt% KB, and 10 wt% La133 (binder) on Al foil. The neat loading mass of DQPZ-3PXZ on Al foil was 2–3 mg cm−2. The electrolytes for Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells were 3 M LiFSI/1.5 M NaFSI/3 M KFSI in TEGDME, respectively. And the volume of the electrolytes was measured by using the formula as follows:

Where ma is the loading mass of active materials, Mw is the molecular weight of DQPZ-3PXZ, n(M+) is the mole number of inserted metal ions (M=Li/Na/K) corresponding to 1 mol DQPZ-3PXZ, n(A-) is the mole number of inserted anions (A = PF6/FSI) corresponding to 1 mol DQPZ-3PXZ, and c(electrolyte) is the concentration of the electrolytes. Therefore, if the electrolytes used in half cells were selected to fabricate the symmetric batteries (1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC/DMC, 2 M NaPF6 in DEGDME, and 2.2 M KPF6 in DEGDME), the theoretical minimum volume values of the electrolytes determined by the formula were 19.4/9.7/8.8 μL for Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells, respectively. And if the electrolytes were 3 M LiFSI in TEGDME, 1.5 M NaFSI in TEGDME, and 3 M KFSI in TEGDME for Li-SBs/Na-SBs/K-SBs, the theoretical minimum volume values of the electrolytes were 6.5/12.9/6.5 μL for Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells, respectively. Considering the wettability of the electrolytes in cathode, anode, and separator, the minimum volume of the electrolytes was set as 50 μL for all Li/Na/K-based symmetric batteries. The separator was Whatman glass fiber (thickness of 0.42 mm). The DQPZ-3PXZ-based electrodes served as both the cathode and anode. At first, we directly combined the two DQPZ-3PXZ electrodes to construct the symmetric cells. The open voltage for all three symmetric cells was nearly zero (0.01 V). Afterward, the Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells were simply activated by charging to 2.5/2.4/2.4 V in the 1st cycle, respectively. No other pretreatment process was carried out or hidden. The cathode:anode mass ratio was 1:0.5. All the symmetric batteries were tested in the atmosphere at room temperature. The working voltages of the Li/Na/K-based symmetric cells were 0.01-2.5/0.01-2.4/0.01-2.4 V. All the observed capacities were reported based on the mass of DQPZ-3PXZ on the cathode side.

Specific capacity calculation

The specific capacity of DQPZ-3PXZ can be calculated using the formula as follows:

The formula above is based on the composition of materials on the electrode (60 wt% DQPZ-3PXZ, 30 wt% KB and 10 wt% La133), where CDQPZ-3PXZ is the specific capacity of DQPZ-3PXZ, Ccell is the observed specific capacity from raw data, W is the total mass of the electrode (excluding aluminum foil), Ccarbon is the specific capacity of the conductive agent.

Energy density calculation

The energy densities of symmetric batteries can be calculated using the formula as follows:

Where It is the recorded capacity (mAh), V is the median voltage (V) read from CT2001A cell test instrument, m(cathode) is the mass of cathode, m(anode) is the mass of anode, m(FSI-) is the mass of FSI- anions inserted in the charge process, m(M+) is the mass of metal ions inserted in the charge process (M=Li/Na/K), CT(PF6−/FSI−) is the theoretical specific capacity of PF6− (185 mAh g−1)/FSI− (149 mAh g−1), CT(M+) is the theoretical specific capacity of Li+ (3860 mAh g−1)/Na+ (1165 mAh g−1)/K+ (685 mAh g−1) ion, respectively.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The experiment data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lu, Y. & Chen, J. Prospects of organic electrode materials for practical lithium batteries. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 127–142 (2020).

Jezowski, P. et al. Safe and recyclable lithium-ion capacitors using sacrificial organic lithium salt. Nat. Mater. 17, 167–173 (2018).

Li, H., Wang, Z. X., Chen, L. Q. & Huang, X. J. Research on advanced materials for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 21, 4593–4607 (2009).

Yu, Y., Chen, C. H., Shui, J. L. & Xie, S. Nickel-foam-supported reticular CoO-Li2O composite anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 44, 7085–7089 (2005).

Zhao, Q., Lu, Y. & Chen, J. Advanced organic electrode materials for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601792 (2017).

Zhu, Y. H. et al. Transformation of rusty stainless-steel meshes into stable, low-cost, and binder-free cathodes for high-performance potassium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 56, 7881–7885 (2017).

Lin, J. et al. A green repair pathway for spent spinel cathode material: Coupled mechanochemistry and solid-phase reactions. eScience 3, 100110 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Manipulation of π-aromatic conjugation in two-dimensional Sn-organic materials for efficient lithium storage. eScience 3, 100094 (2023).

Hong, Y. et al. A universal small-molecule organic cathode for high-performance Li/Na/K-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 52, 61–68 (2022).

Lee, M. et al. High-performance sodium–organic battery by realizing four-sodium storage in disodium rhodizonate. Nat. Energy 2, 861–868 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Using an organic acid as a universal anode for highly efficient Li-ion, Na-ion and K-ion batteries. Org. Electron 62, 536–541 (2018).

Liu, S. H. et al. Electrolyte effect on a polyanionic organic anode for pure organic K-ion batteries. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 38315–38324 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Ultra-stable, ultra-long-lifespan and ultra-high-rate Na-ion batteries using small-molecule organic cathodes. Energy Storage Mater. 41, 738–747 (2021).

Guo, C. Y., Zhang, K., Zhao, Q., Peia, L. K. & Chen, J. High-performance sodium batteries with the 9,10-anthraquinone/CMK-3 cathode and an ether-based electrolyte. Chem. Commun. 51, 10244–10247 (2015).

Gao, H. C., Xue, L. G., Xin, S. & Goodenough, J. B. A high-energy-density potassium battery with a polymer-gel electrolyte and a polyaniline cathode. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 57, 5449–5453 (2018).

Yu, Q. et al. Novel low-cost, high-energy-density (>700 Wh kg−1) Li-rich organic cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 415, 128509 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Benzene-bridged anthraquinones as a high-rate and long-lifespan organic cathode for advanced Na-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 426, 131251 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. In situ quantification of interphasial chemistry in Li-ion battery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 50–56 (2019).

Yamada, Y. et al. Unusual stability of Acetonitrile-based superconcentrated electrolytes for fast-charging Lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5039–5046 (2014).

Obrezkov, F. A., Shestakov, A. F., Traven, V. F., Stevenson, K. J. & Troshin, P. A. An ultrafast charging polyphenylamine-based cathode material for high rate lithium, sodium and potassium batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 11430–11437 (2019).

Kapaev, R. R., Scherbakov, A. G., Shestakov, A. F., Stevenson, K. J. & Troshin, P. A. m-Phenylenediamine as a building block for polyimide battery cathode materials. ACS Appl Energ. Mater. 4, 4465–4472 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Electrochemical study of Poly(2,6-Anthraquinonyl Sulfide) as cathode for alkali-metal-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2002780 (2020).

Häupler, B. et al. Aqueous zinc-organic polymer battery with a high rate performance and long lifetime. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e283 (2016).

Patil, N. et al. An ultrahigh performance zinc-organic battery using Poly(catechol) cathode in Zn(TFSI)2-based concentrated aqueous electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100939 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. A polymer/graphene composite cathode with active carbonyls and secondary amine moieties for high-performance aqueous Zn-organic batteries involving dual-ion mechanism. Small 17, 2100902 (2021).

Wang, X., Xiao, J. & Tang, W. Hydroquinone versus Pyrocatechol pendants twisted conjugated polymer cathodes for high-performance and robust aqueous Zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2108225 (2022).

Hu, Y. et al. Novel insoluble organic cathodes for advanced organic K-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000675 (2020).

Wang, X. X. et al. Insoluble small-molecule organic cathodes for highly efficient pure-organic Li-ion batteries. Green. Chem. 23, 6090–6100 (2021).

Yu, F. et al. Organic-Carbon core–shell structure promotes cathode performance for Na-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300740 (2023).

Matsunaga, T., Kubota, T., Sugimoto, T. & Satoh, M. High-performance lithium secondary batteries using cathode active materials of triquinoxalinylenes exhibiting six electron migration. Chem. Lett. 40, 750–752 (2011).

Kapaev, R. R., Zhidkov, I. S., Kurmaev, E. Z., Stevenson, K. J. & Troshin, P. A. Hexaazatriphenylene-based polymer cathode for fast and stable lithium-, sodium- and potassium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 22596–22603 (2019).

Otteny, F. et al. Poly(vinylphenoxazine) as fast-charging cathode material for organic batteries. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 8, 238–247 (2020).

Lee, K. et al. Phenoxazine as a high-voltage p-type redox center for organic battery cathode materials: small structural reorganization for faster charging and narrow operating voltage. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4142–4156 (2020).

Zhang, X. Y., Xu, Q. H., Wang, S. J., Tang, Y. C. & Huang, X. B. One-step synthesis of a polymer cathode material containing phenoxazine with high performance for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl Energ. Mater. 4, 11787–11792 (2021).

Placke, T. et al. Reversible Intercalation of Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide anions from an ionic liquid electrolyte into graphite for high performance dual-ion cells. J. Electrochem Soc. 159, A1755–A1765 (2012).

Plashnitsa, L. S., Kobayashi, E., Noguchi, Y., Okada, S. & Yamaki, J. Performance of NASICON Symmetric Cell With Ionic Liquid Electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A536–A543 (2010).

Plashnitsa, L. S., Kobayashi, E., Okada, S. & Yamaki, J. Symmetric lithium-ion cell based on lithium vanadium fluorophosphate with ionic liquid electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 56, 1344–1351 (2011).

Chen, H. Y. et al. Lithium salt of Tetrahydroxybenzoquinone: Toward the Development Of A Sustainable Li-ion Battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8984–8988 (2009).

Shiwen et al. All organic Sodium-ion batteries with Na4C8H2O6. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 126, 6002–6006 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. A p-n fusion strategy to design bipolar organic materials for high-energy-density symmetric batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 14485–14494 (2021).

Chen, J.-J. et al. Design and performance of rechargeable sodium ion batteries, and symmetrical Li-ion batteries with supercapacitor-like power density based upon Polyoxovanadates. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701021 (2018).

Carlin, R. T., De Long, H. C., Fuller, J. & Trulove, P. C. Dual intercalating molten electrolyte batteries. J. Electrochem Soc. 141, L73 (1994).

Li, X., Ou, X. & Tang, Y. 6.0 V high-voltage and concentrated electrolyte toward high energy density K-based dual-graphite battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2002567 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Constructing the best symmetric full K-ion battery with the NASICON-type K3V2(PO4)3. Nano Energy 60, 432–439 (2019).

Wang, J., Lee, Y., Tee, K., Riduan, S. N. & Zhang, Y. A nanoporous sulfur-bridged hexaazatrinaphthylene framework as an organic cathode for lithium ion batteries with well-balanced electrochemical performance. Chem. Commun. 54, 7681–7684 (2018).

Wu, M.-S. et al. Supramolecular self-assembled multi-electron-acceptor organic molecule as high-performance cathode material for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100330 (2021).

Kuan, H. C. et al. A nitrogen- and carbonyl-rich conjugated small-molecule organic cathode for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 16249–16257 (2022).

Peng, C. et al. Reversible multi-electron redox chemistry of π-conjugated N-containing heteroaromatic molecule-based organic cathodes. Nat. Energy 2, 17074 (2017).

Yang, X. et al. Mesoporous Polyimide-linked covalent organic framework with multiple Redox-active sites for high-performance cathodic Li storage. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 61, e202207043 (2022).

Dai, Y. et al. High-capacity proton battery based on π-conjugated N-containing organic compound. Electrochim. Acta 442, 141870 (2023).

Tie, Z. W., Liu, L. J., Deng, S. Z., Zhao, D. B. & Niu, Z. Q. Proton insertion chemistry of a Zinc-organic battery. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 59, 4920–4924 (2020).

Li, S. W. et al. A stable covalent organic framework cathode enables ultra-long cycle life for alkali and multivalent metal rechargeable batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 48, 439–446 (2022).

Wei, B. et al. Design of bipolar polymer electrodes for symmetric Li-dual-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 451, 138773 (2023).

Yin, Q.-M. et al. Mn-rich Phosphate cathode for sodium-ion batteries: anion-regulated solid solution behavior and long-term cycle life. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304046 (2023).

Li, D., Tang, W., Wang, C. & Fan, C. A polyanionic organic cathode for highly efficient K-ion full batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 105, 106509 (2019).

Augustyn, V. et al. High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 12, 518–522 (2013).

Simon, P., Gogotsi, Y. & Dunn, B. Where do batteries end and supercapacitors begin? Science 343, 1210–1211 (2014).

Aurbach, D., Markovsky, B., Shechter, A., EinEli, Y. & Cohen, H. A comparative study of synthetic graphite and Li electrodes in electrolyte solutions based on ethylene carbonate dimethyl carbonate mixtures. J. Electrochem Soc. 143, 3809–3820 (1996).

Weber, W. et al. Ion and gas chromatography mass spectrometry investigations of organophosphates in lithium ion battery electrolytes by electrochemical aging at elevated cathode potentials. J. Power Sources 306, 193–199 (2016).

Guo, Z. et al. Toward full utilization and stable cycling of polyaniline cathode for nonaqueous rechargeable batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301520 (2023).

Eshetu, G. G. et al. In-depth interfacial chemistry and reactivity focused investigation of lithium-imide- and lithium-imidazole-based electrolytes. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 8, 16087–16100 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of UESTC (ZYGX2019J027), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant NO. 52173236), and the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (NO.2023NSFSC0410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J.L. designed the molecule, carried out all the experiments, collected the data, and wrote the raw paper; H.L.M., W.T., K.X.F., S.J., J.G., M.W. and Y.W. all participated in the analysis of the experimental results; B.C performed the quantum calculations; C.F. revised the paper, proposed and supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Ma, H., Tang, W. et al. Single organic electrode for multi-system dual-ion symmetric batteries. Nat Commun 15, 9533 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53803-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53803-3